In the summer, birds will open their wings, find shade, take to the water, and engage in gular fluttering (panting) just to stay cool.

Birds are amazing animals that have developed significant adaptations to the environments around them. This includes the adaptations that wild birds make when the summer season comes around — changes that help them keep their body temperatures at comfortable levels. But how do wild birds keep cool in summer? This article will break down the different measures birds take to keep from getting too hot in the summer months, as well as explore their physiology and why they behave like they do when the heat is on.

Overview: Bird Anatomy

You probably are aware that wild birds do not have quite the same anatomy as other animals — all birds, of course, have wings, for instance — but the differences between birds and other animals (like mammals and humans) go deeper than that.

First of all, if you were to compare the average body temperature of a human to that of a bird, you would have your first difference. Human beings on average have a temperature of around 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit.

Birds, on the other hand, have average body temperatures of 102 to 109 degrees Fahrenheit, with some birds like the Golden-crowned kinglet (REGULUS SATRAPA) reaching temperatures of 111 degrees Fahrenheit.

Higher body average temperatures can mean that a bird (a warm-blooded animal) does not have too much room to endure elevated temperatures on summer days. If a bird becomes overheated, this can damage its neural system and cause dehydration, and the loss of perching or flight abilities.

The second difference between birds and other animals (like mammals) is that birds do not have sweat glands. They instead lose heat (and some moisture) through their skin, but this is often not enough to truly cool a bird down to its ideal body temperature on hot summer days.

Another physiological difference between birds and other mammals is their bills or beaks. A bird’s bill or beak may be larger if it lives in warmer climates — and this can benefit the bird in some respects when cooling down. Birds also have feathers — which they can adjust when it gets too hot.

The final major difference between birds and other animals may have been stated already — and it is obvious — but they do have wings. When it comes to the summer, a bird can use its wings to cool down in the heat, in different ways.

How Do Birds Keep Cool in Summer ?

So with an understanding of a bird’s anatomy, you still may be wondering “how do wild birds keep cool in summer?”. And that would be a good question; because wild birds do a number of things to keep their cool.

These include a number of different behaviors, depending on the bird species — but for the most part, birds in the wild behave in similar ways when it comes to the heat of the summer months.

These include behaviors like thermoregulation, feather adjustment, gular fluttering, finding shady areas, and taking to the water. These behaviors are explained in the next section, below.

Thermoregulation

The overall idea for birds — like most warm-blooded animals — during the hot weather of the summer months is to adjust their body temperatures so that it matches that of their surroundings.

This process is also known as THERMOREGULATION. In hot weather, wild birds must lose excess heat without the help of sweat glands, meaning, they must find other ways to lose heat without a ready source of water (i.e. sweat) that evaporates from a skin surface, taking away heat from the body.

Some birds will perform different behaviors to mimic the effect of sweat. The Black Vulture (CORAGYPS ATRATUS) and the White Stork (CICONIA CICONIA) will undergo UROHIDROSIS — where they will excrete (urinate) onto their legs. The moisture from the excretion evaporates and cools the bird’s body.

Other birds will thermoregulate through a deliberate positioning of their bodies. The Herring Gull (LARUS ARGENTATUS) is known for its gray/black back and white chest/head. When it is nesting on hot days, it will purposefully face the sun so that light is reflected off of its lighter body parts.

A tropical bird like a Toucan (of the family RAMPHASTIDAE) will use its large beak to radiate a high degree of heat from the bird’s body when the outside temperature gets too hot. This is caused by an increased blood flow directly to the beak, which emanates the excess heat from the toucan.

Feather and Wing Adjustment

A bird’s feathers are not unlike the hair on a mammal. They are comprised of dead cells that are made of a protein called keratin; the bases of the feathers are attached to follicles in the bird’s skin.

When a bird wants to, it can contract its muscles and draw its feathers closer to each other. In reverse, the bird can relax its muscles and spread its feathers further apart. This is the case on hot summer days — when a bird may need as much skin area exposed as possible to expel excess heat.

That said, a bird may also simply adjust its wings to provide further cooling surface area to its body. The Great Blue Heron (ARDEA HERODIAS) is known to stretch its wings out on hot days to lower its body temperature. More surface area means more chances for heat to escape.

Birds like songbirds may flutter their wings rapidly in hot weather to improve overall circulation and cool down a little. This is primarily to expose the bird’s skin to lose heat — a similar idea as spreading its feathers.

Gular Fluttering (Panting)

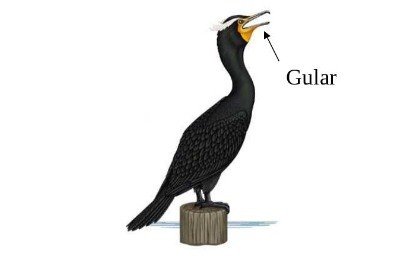

If you are still wondering “how do wild birds keep cool in summer?” you won’t have the complete picture until you understand gular fluttering. Gular fluttering is the process by which a bird opens its mouth and exhales, letting hot exhalation pass by its moist throat tissues.

A bird will vibrate its throat tissues as the exhaled gas passes through. This allows the throat moisture to evaporate somewhat and take the heat along with it. Gular fluttering, for this reason, is compared to when an animal like a dog pants in hot weather.

Various bird species have been noted to exhibit this behavior including Mourning Doves (ZENAIDA MACROURA), Owls (of the family STRIGIFORMES), and Double-Crested Cormorants (PHALACROCORAX AURITUS).

Taking To The Shade

Birds will also take to cooler places when it gets too hot in the summer — another way that they may “use” their wings to cool down. This includes places like the shady areas under deciduous trees, in or under bushes, near the base of shrubs, and in the shade of buildings and building crevices.

The process of “cooling down” may begin much earlier than when a songbird takes to the shade. Birds such as mockingbirds, cardinals, catbirds, and orioles have been observed to limit their singing/chirping activity during long summer days, preferring the early morning or late afternoon.

The Burrowing Owl (ATHENE CUNICULARIA) inhabits the grasslands, deserts, and herding agricultural areas of the Americas. It is known to occupy the burrows of prairie dogs during hot summer days. The owl even creates its nests in these burrows, out of the sun and in the cooling shade.

Taking to The Water

Finally, a bird will take to the water to keep cool in the summer. Songbirds have been known to enjoy birdbaths, flying to them and dousing their heads, legs, and bodies in the water just to cool off. This is even the case if the birdbath is comparatively shallow or does not contain much water.

The Whooping Crane (GRUS AMERICANA) inhabits the wetlands and marshlands of North America. It is a large bird that has long legs from which heat can readily radiate away. The whooping crane will stand in deeper water to cool down, as well as shade its body with outstretched wings.

Other birds can not take to the water as easily, but they have their own ways of dealing with the summer heat. The Roadrunner (of the genus GEOCOCCYX) is typically a desert animal that may go for long periods without seeing bodies of water.

This, however, is offset by the fact that roadrunners use their diet (lizards, rodents, birds, eggs, snakes, scorpions, among other things) to stay hydrated. Salt glands near their eyes help get rid of the build-up excess salt in their diets, keeping the roadrunner hydrated.

Conclusion

Wild birds will exhibit a number of diverse behaviors to keep cool during the summer, but some near-universal behaviors seem to be cooling through gular fluttering, feather adjustment, and an increased presence in shade and water.

As warm-blooded creatures, birds will find almost any way to cool down, from burrowing, to beak and wing thermoregulation, to urohidrosis. Using these techniques, wild birds have an excellent chance of keeping their core temperatures at comfortable levels and truly beating the heat.